The global response to George Floyd’s death has got people talking about other incidents where white people did bad things to Black people. One of those incidents surfaced in a viral video of a white woman threatening to call the police, then doing so, on a bird-watching African-American man who asked her to leash her dog in New York’s Central Park. Amy Cooper’s apology to Christian Cooper (no relation), following her being fired, is a classic case of too little waaaay to late.

In his New York Times article, How White Women Use Themselves as Instruments of Terror, Charles M. Blow argues that what Cooper did was simply the latest in a long history of white women using themselves as weapons against Black men. And Blow adds, “There are too many noosed necks, charred bodies and drowned souls for them to deny knowing precisely what they are doing.” I agree and here’s why…

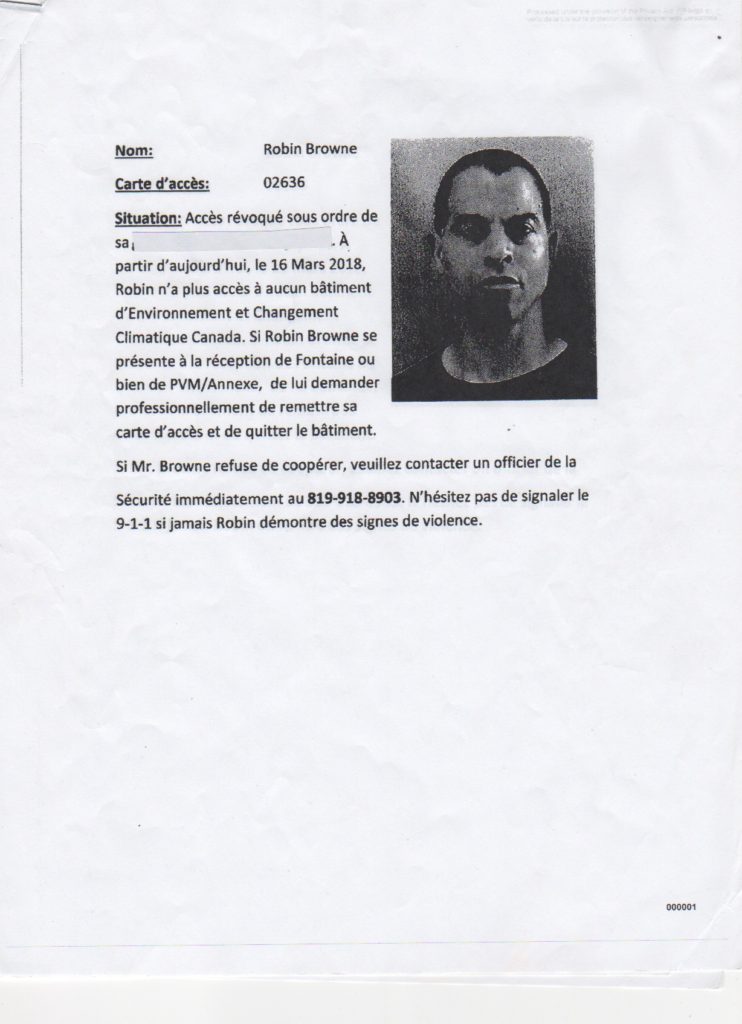

In the fall of 2017, I got a new boss. She was my sixth boss in 18 months and she immediately began micromanaging me on a level that, to me, qualified as my first case of professional harassment. I told my union representative about it and he told me he had informed the Director General. I heard nothing from the DG for about a month while the situation with my boss worsened. Then, one day, after a tense email exchange with my boss, I went to a meeting in a boardroom full of my colleagues, who were mostly white women. When I entered the meeting, I saw my boss sitting at the table, went to her and asked, “Was my email clear?”. I was angry and tense when I said it. In response, she sent an email to my DG that said, “He is getting in my face in a threatening way.” (I got the email through Access to Information – i.e. the federal government equivalent of taking part in a slave rebellion.) A few minutes later, my DG entered the room, came over to where I was sitting silently in the corner and said, in front of all my colleagues, “ Robin. Do you have an issue? Because we can’t have you threatening your colleagues.” (This is the same person who, as I explained in Tales from the Plantation #1, had me banned from all of my workplace buildings without informing me.)

Despite the many complaints I have filed since that day, neither my former boss nor the DG have been held accountable, in fact, the DG got promoted. The global reaction to George Floyd’s death provides some perspective on why that is.

Systemic discrimination means it’s normalized. Black folks suffer it every day. It’s not unusual. It’s not spectacular – and it’s rarely, if ever, filmed. However, like the cops who killed Floyd, the people abusing Black folks in the federal public service know exactly what they’re doing.

Blow’s argument that white women know what they’re doing is counter to the idea of “unconscious bias” that is so popular in government discussions of systemic discrimination. The idea is that, since the bias is unconscious, all we have to do is make it conscious for people through awareness training and all will be well.

However, my experience shows that isn’t the case. All that great awareness I’ve raised by taking the risk to speak out and file complaints has only made my harassers more aware that what they’re doing is wrong – but hasn’t stopped them from doing it. It has also resulted in me being hit by one sanction after another for the last two years.

That’s because systemic discrimination privileges certain groups over others and those on top don’t want to share the goodies. We must recognize that folks act in their own interest so, to get them to do the right thing in terms of diversity and inclusion, we have to change the system so that there are much bigger rewards for doing the right thing – and much bigger penalties for doing the wrong thing.

They should start by setting targets for executives, like actually hitting their legally mandated Employment Equity Act numbers by hiring, and promoting, all the talented Black folks around, and withholding their performance bonuses if they don’t.

Black lives matter – but docking performance pay gets results.